Every year, as the first monsoon showers sweep across Mumbai, something quietly stirs in the landscape around me. The streets grow darker, the air gets heavy with petrichor, and familiar trees start to put on their seasonal show. One such tree is Kaim (Mitragyna parvifolia) or True Kadamba. Kaim is often confused with the other Kadamba, Neolamarckia cadamba, which belongs to the same family, Rubiaceae, and folks often debate over which is the true Kadamba.

Image 1: Kaim (Mitragyna parvifolia) tree habit

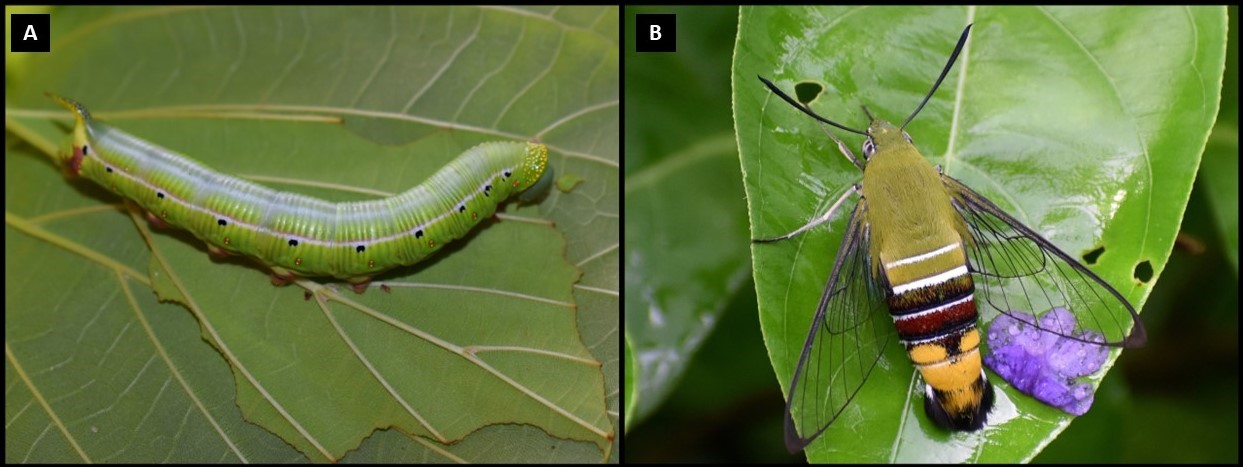

For most part of the year, Kaim isn’t the most flamboyant tree, but watch closely during the monsoon, and you’ll find that it turns into a miniature nursery. Around August each year, two beautiful insects visit the tree to lay their eggs. First, the elusive Pellucid hawkmoth (Cephonodes hylas), and the strikingly colourful Commander butterfly (Moduza procris). Interestingly, from February through mid-May—the dry pre-monsoon months—few early-stage insects are seen in the area (as recorded through my own sightings and the local iNaturalist data for these two species). It’s as if they both wait patiently for that familiar cue: the first burst of rain and the flush of young leaves. As soon as the rain subsides, the Commander butterfly comes into the region, gliding confidently, females pausing to lay a single egg on the underside of a young Kadamba leaf. Meanwhile, the Pellucid hawkmoth females, so fast and hard to follow when in flight, quietly place their green, round eggs on the same tree.

But this year, something strange happened. The rains arrived early in Mumbai—by the end of May, pouring rather heavily for a week — and just days into June, I found something unusual: fresh Pellucid hawkmoth eggs and early instar Commander larvae already feeding on the Kadamba leaves. This was at least a couple of months earlier than what I’ve recorded in previous years. Their earlier appearance made me pause. Was this a one-off response to a transient low-pressure belt or unusual local conditions? Or is this a subtle signal of broader environmental change—a shift in seasonal patterns driven by increasing urban heat, changing rainfall rhythms? But then I quickly reminded myself: this is just one year. We can’t jump to conclusions from a single early arrival. The monsoon’s timing can vary naturally, sometimes influenced by a temporarily altered microclimate. Nonetheless, I continued observing the plant and the two insects as they matured through their life course.

Image 2: Pellucid hawkmoth (above) and Commander butterfly (below) matured from the ones I saw in June

My early June sighting might not change the world—but it sparked a series of questions that could. And that’s exactly where repeated, periodic observations of our neighbourhood life-forms matter so much. By watching the same plants and insects across years, we can start to build a clearer picture of what’s changing—and how fast. This is where community-driven platforms like Seasonwatch allow individuals to track local phenological patterns while contributing to a larger network of ecological knowledge. So, the next time you walk past a flowering tree after the rain, take a moment to pause and look around. You never know—you might find an oddly coloured flower or half-eaten leaf that could be a clue to something much bigger. After all, even the smallest observation can start a ripple— a butterfly effect —towards conservation.

About the author: Gaurav Soman is a Mumbai-based naturalist working towards urban wildlife conservation using citizen Science tools. Through his self-supported project ‘Butterflies of Mulund’, he continues to learn more about the local pollinator diversity, often creating awareness through nature walks and educational content.

Very informative and interesting article Gaurav. Fantastic 😍!